It began innocuously enough when the incoming priest at St. Catherine of Siena Catholic Student Center at Drake University noticed a piece of paper on a copy machine in the parish office.

On it was a counselor's authorization of hormone therapy for a transgendered person about to undergo a sex change. On a letterhead that included the center's name and address.

What came quickly after is changing a community:

The intervention of the bishop, worried about liability for the Diocese of Des Moines. The firing of the transgendered woman who worked part time as parish housekeeper and who, as an independent social worker, used parish offices to provide counseling for transgendered clients. Nearly 100 parishioners organizing separate prayer services instead of going to Mass because they said they sought a welcoming place for all. And angst in a once-tight faith community about how the church should minister to those whose lifestyles aren't condoned by the church.

Some in the parish believe the Catholic Church must adhere to 2,000 years of teaching because, even in a changing world, what kind of religion is permissive of everything? Others believe the church should welcome everyone because, after all, isn't that what Jesus did?

"It brought up these other issues: 'What's the place for people who have alternative lifestyles, whether they're transgender or homosexual?' " said Phil James, who recently left St. Catherine's, partly because of the controversy, partly because the father of three wanted a parish with more children.

"Clearly, they had reason to fire this woman," he said. "But the perception opened up a lot of wounds about the Catholic Church in general. ... We want to be a welcoming Christian faith, but how is that possible when we kick people out that aren't like us? That's the perception, anyway. I'm not saying it's real."

His father, parishioner Larry James Sr., sees the firing as straightforward.

"I believe bishop couldn't have done anything else," James Sr. said, even though he believes the counselor helped people and the fallout hurt. "It was tough on the church and tough on the priest and bishop, because they truly had empathy for that woman."

The person who sparked the divide is Susan McIntyre, 57, who for 10 years worked as a housekeeper at the student center. Many didn't know it, but the quiet woman who kept the place spick-and-span used to be named Jim Ford. In 1988, he had gender-reassignment surgery and became Susan McIntyre. (In the eyes of the Vatican, McIntyre is still a man.)

McIntyre converted to Catholicism in the 1990s. A few years ago, the priest at St. Catherine's gave her permission to use parish space to see counseling clients on Saturday mornings, she said. McIntyre never spoke directly to the priest about being transgendered, but she believes he knew. She formed a transgender support group that met at the church, and the priest, Jim Laurenzo, sometimes stopped by the support group to say hello, McIntyre said. (Laurenzo, now retired, did not return telephone messages.)

Then the parish - a Newman Center, which ministers to students at the non-Catholic university as well as the nonstudent community - got a new priest, Joel McNeil. McNeil spotted the letter on the copy machine, took it to the bishop, and found himself in a sticky situation.

"He's not on the same page as people like me, but he is a good person who came into a hornet's nest," said parishioner Mary Kay Shanley, who describes St. Catherine's as liberal. "We're very aware of the rules of the Roman Catholic Church. But maybe if we had a theme song, I've often thought it would be one we sing at church that's called, 'All Are Welcome in This Place.' "

To McNeil, though, the theological discussion arising from the firing is about much more than one parish's bent toward inclusiveness. It's about 2,000 years of consistent church teaching.

"All are welcome, but not everything goes," McNeil said. "The bottom line is: What does Jesus want? And here at a Catholic church, we understand Christianity in a historical context. We are not free to reinvent Christianity."

On its surface, what some in the church call "the Susan McIntyre affair" is a simple case of a person overstepping her bounds and putting the diocese in a precarious situation regarding liability.

Richard Pates, bishop of Des Moines, mailed McIntyre a three-sentence termination letter saying her firing was based on "your unauthorized representation indicating that you are employed by and operating on behalf of the Newman Center as a counselor or social worker." Nowhere does the letter refer to gender identity.

In an interview, Pates called the matter a personnel issue, nothing more.

Susan McIntyre admits her life has been weird.

Born Jim Ford, he grew up on Des Moines' east side, a sensitive boy who sometimes broke into tears at a beautiful sunset. As a lifeguard, Ford once saved a 15-year-old from drowning. But every time he looked in a mirror, the image looked different from what he felt inside.

He got a master's degree in social work from the University of Iowa, then a job with psychiatric patients at Broadlawns Medical Center: "I'd always wanted to work with the sickest of the sick and the poorest of the poor."

Ford was working at the hospital in 1987 when he witnessed a patient's death. With that came a profound understanding that life is fleeting. He decided it was time to be his true self, and Ford became Susan McIntyre. She began an independent counseling practice - the only transgendered licensed independent social worker in Iowa, she said - to help other transgendered people.

"I would have died," likely committing suicide, without the sex change, she said. "I wanted my outsides to match my insides."

As McIntyre, she felt at home in the Catholic faith, even with its teachings that homosexual behavior and some types of sexual reassignment are sins.

Under church teachings, a transgendered person with ambiguous sexual organs may have surgery to correct the problem. However, in McIntyre's case, she felt her brain and soul were born female, but not the sexual organs. The church believes cases like McIntyre's are psychological and calls sex-change surgery mutilation.

Pates said the church's views on homosexuality and transgenderism fall in line with two millennia of teaching, part and parcel with its overall stance on human sexuality: that sex should be reserved for marriage between a man and a woman, and in cooperation with God to create new life. Any sexual act outside marriage is thus sinful.

McIntyre has found Catholicism a deep faith and loved the tradition even as she hated some of the church's views. Once she wrote to Pope John Paul II about the pain caused by the church's teachings on transgendered people.

Why would McIntyre convert to a faith that deems a sin something she believes is integral to her identity?

Internally, she says, she always thought of herself as a woman. She believed the church's view on transgendered people doesn't acknowledge modern science and that, in time, it would change. And she saw so much good in her new faith that she didn't want one teaching to push her away.

And so McIntyre got the job at St. Catherine of Siena and asked the priest to use church space for counseling. McIntyre said she never represented her counseling as being done through the church but admits to using the parish name and address on letterhead.

"It wasn't a secret," she said. "I was actually proud of it. I was doing a service for folks who were incredibly poor."

Then, in late September, the bishop's secretary asked McIntyre to visit the next day. In a 15-minute meeting with the bishop and his attorney, McIntyre was fired.

She cried for a month, feeling as if her church family had rejected her. She tried to get a lawyer, but none would take her case, she said.

McIntyre believes the real issue isn't about her; it's about how the church responds to homosexuals and transgendered people. There's a movement in psychiatric circles to reclassify transgenderism as a medical condition instead of a mental illness, similar to a movement that two decades ago succeeded in removing homosexuality from a list of mental disorders.

"The bishop made it pretty clear that I was not welcome," McIntyre said. "(So) can I be Catholic, or actually not? That's what the big deal is."

For defenders of the Catholic Church, the McIntyre case is open and shut.

Bishop Pates said that McIntyre's firing as parish janitor was based on her representing her counseling services as being under the auspices of the church. It had nothing to do with her gender identity.

"We want to be very, very clear this instance is strictly a personnel issue," Pates said.

Diocesan attorney Frank Harty said McIntyre's use of letterhead that made it appear she was a church counselor violated her professional code of ethics as a licensed social worker, even if she had the priest's permission. That exposed the diocese to a potential lawsuit if, say, McIntyre counseled someone going through a sex change and the person later regretted doing so, Harty said.

Some in the parish were angry that McIntyre was fired as housekeeper instead of just being told to quit counseling on church property, and they told the bishop so in a meeting he held with about 60 parishioners.

Eric Morse, a liturgy coordinator at the parish who is searching for another church home, holds that view.

"The bishop just brought the hammer down on her instead of being a Christian and showing her some mercy. The Christian way to handle this was to tell Susan she would not be able to do counseling at the church any more. ... That punishment was too great for the crime."

According to McNeil, the bishop considered other alternatives in consultation with the diocesan attorney. But since McIntyre's counseling practice put the diocese at risk of a liability lawsuit, McNeil said, the diocese decided firing was the most appropriate measure.

In a room just inside the doors of St. Catherine of Siena parish recently, McNeil spoke about his tumultuous first few months as pastor. He knows this situation can be painted as the powerful Catholic Church trampling on a housekeeper's individual rights. But he rankled at some parishioners' comments that this incident showed St. Catherine's had become an unwelcoming place.

There's a sign out front of the church that identifies it as Catholic, McNeil noted. It's a matter of truth in advertising, he said: Would the parish stick by Catholic teachings or have a set of beliefs that went outside the Catholic tent?

"For a person who sees Christianity as fidelity to what Christ began 2,000 years ago, we can't change that teaching," he said.

Part of the Catholic belief, McNeil said, is that those who are oriented to homosexuality are called to lives of chastity, and those who believe their inward gender is different from their outward gender must battle that as a psychological problem, not with surgery.

"Heresy is overstressing one truth at the expense of other truths," McNeil said. "There is some truth that the church must be welcoming, but not to the point where it ceases being the church."

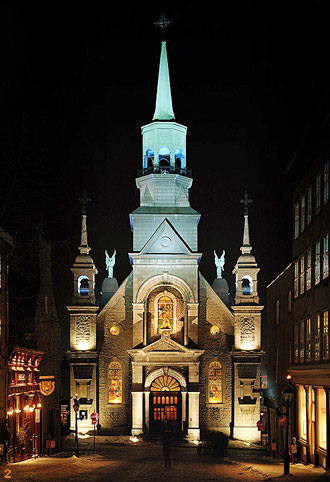

Three-hundred families make up the nonstudent parishioners at St. Catherine of Siena, the parish where former Gov. Tom Vilsack attended Mass before moving to Washington, D.C. The church was born in a room above the Varsity Theater in 1969 and dedicated to supporting Catholic students at Drake. Students come Sunday nights for a home-cooked meal.

The parish gained a reputation as a congregation with an appetite for social justice. Members traveled to El Salvador to rebuild a church destroyed by an earthquake.

For its parishioners, the McIntyre matter has involved more than liability or church doctrine.

It was personal, and it has hurt.

"It's just gut-wrenching for me and a lot of other people in the parish," said parishioner Larry James Sr., who supports the bishop's actions.

McNeil is confident that his parish is already rebounding from its rough patch. The arrival of a new priest always brings difficulties, he said, and McIntyre's situation exacerbated them.

He hopes the parish recalibrates in coming months, having strayed too far left in the Catholic spectrum.

Shanley, the parishioner who described herself as "not on the same page" with McNeil, acknowledged that "the bishop is doing his job." Then she added, "But most of us wish we could have been left alone."

Additional Facts

National views

John Haas, president of the National Catholic Bioethics Center, said that transgendered people have a psychological disorder, and that surgery to change one's gender is offensive to God.

His independent organization, which directly follows the teachings of the Catholic Church, promotes "human dignity in health care and the life sciences."

"We would say this is a gravely disordered act, an assault upon God's creation, an act of mutilation that renders an otherwise healthy body dysfunctional," Haas said. "There can be surgical interventions to heal, cure or overcome pathologies to save lives. If it doesn't hold to those ends, the church holds them to be acts of mutilation."

Haas said transgendered people who have had sexual reassignment surgery should not receive communion in the church unless they have repented.

Marianne Duddy-Burke, executive director of DignityUSA, an organization of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender Catholics, has heard of two situations nationally where unpaid volunteers lost their ministry jobs at Catholic parishes after telling a priest they were switching their gender. In a third situation, a paid transgender organist was fired after he began to dress as a woman.

"Transgender people fight the experience of exclusion and misunderstanding, and the fear of being exposed so often in their lives," Duddy-Burke said. "I can only imagine the pain of no longer having a home in the parish."

Asked about church teachings that prohibit what her organization stands for, Duddy-Burke said the question turns on how you define "the church." Many people equate the Catholic Church with the leadership and the hierarchy, Duddy-Burke said, but she believes the Catholic Church is "the broad people of God." It's an example of pastoral practice versus doctrinalism, she said.

(Your Opinions on the matter are sought)