Wednesday, December 31, 2008

Ordination of a close family member

I have been away this Christmas to attend the ordination of a dear family member who was ordained a priest. He belongs to the order which is called the Heralds of the Gospel a link of which can be found at the link list of this blog.

Below I am embedding 2 videos of the ordination. It would be really nice if my readers could visit the TV website of the Heralds of the Gosple at TV Arautos

Friday, December 12, 2008

Our Lady of Guadalupe – 12 December 2008

Biographical Section

These are some of the dialogues between Our Lady and Juan Diego, taken from written narrations inspired by the account of Indian scholar Antonio Valeriano around the middle of the 16th century.

In the first apparition, Our Lady addressed Juan Diego, speaking in the Mexican idiom: “Juanito, my son, the humblest of my children, where are you going?"

"Noble lady, I go to the church in Tlatelolco to listen to such divine matters as our priests teach us," he replied.

She said, “Know for certain, dearest of my sons, that I am the perfect and ever-Virgin Mary, Mother of the true God, the Lord of all things and Master of Heaven and Earth. I ardently desire a temple to be built here, where I will show and offer all my love, compassion, help, and protection to the people and those who look for me. I am your merciful Mother, the Mother of all who live in this land and of all mankind. I will hear the weeping and sorrows of those who love me, cry to me, and have confidence in me, and I will give them consolation and relief.

“Therefore, so that my designs might be fulfilled, go to the house of the Bishop of Mexico City and tell him that I sent you, and that it is my desire to have a temple built in this place. Tell him all that you have seen and heard. Be assured that I shall be grateful and will reward you for diligently carrying out what I have asked of you.”

Juan Diego bowed low and said, “My holy one, my Lady, I will go now and do all that you ask of me. Thy humble servant bids thee farewell.”

The second apparition: That same afternoon Juan Diego returned to the hilltop from the Bishop’s palace where he had delivered the message. The Holy Virgin was waiting for him. He told her:

“Noble lady and most loved Mistress, I did what you commanded. Even though it was difficult to be admitted to speak with the Bishop, I saw His Excellency and communicated to him your message. He received me kindly and listened with attention. But when he answered me, it seemed as if he did not believe me. …

“So I beg you, noble Lady, entrust this message to someone of importance, someone well-known and respected, so that they might believe in him. For I am a nobody, a piece of straw, a lowly peasant, and you, my Lady, have sent me to a place where I have no standing. Forgive me if my answer has caused you grief or displeasure, my Lady and my Mistress.”

The third apparition: The Holy Virgin insisted that she wanted Juan Diego to give her message to the Bishop. He did so, and this time the Indian returned to Our Lady saying that the Bishop had asked for a sign to prove that what he said was true.

Our Lady told him: “Very well, my dear little one, return here tomorrow and you will take to the Bishop the sign he has requested. With this he will believe you and no longer doubt you or be suspicious of you. Know, my beloved little one, that I will reward your solicitude, effort and fatigue spent on my behalf. Go now. I will await you here tomorrow.”

The fourth apparition: The next day, instead of going to the hilltop, Juan Diego took a different route that bypassed it to find a priest for his uncle who was gravely ill. Juan Diego was certain that Our Lady would not see him.

But she appeared to him along the road he had taken and asked him: “What is this, my little son? Where are you going?”

Juan Diego answered: “My loved Lady, God keep you! How are you this morning? Is your health good, my dearest Lady? It will grieve you to hear what I have to say. My uncle, your poor servant, is sick. He has taken the plague and is near death. I am hurrying to your house in Mexico City to call a priest to hear his confession and give him the last rites. When I have done this, I will return here immediately so I may deliver your message. Forgive me, I beg you, my Lady, be patient with me for now. I will not deceive you and tomorrow I will come in all haste.”

She answered: “Listen to what I am going to tell you, my son, and let not your heart be disturbed. Do not fear that plague or any other sickness or anguish. Am I not here, I, who am your mother? Are you not under my protection and care? Am I not your life and health? Are you not in the folds of my mantle and the embrace of my arms? What else do you need? Do not be grieved or disturbed by anything.”

She then told him that he should not worry about the sickness of his uncle, for he would not die at this time and that, in fact, he was already cured.

Calling herself Holy Mary of Guadalupe, she told Juan Diego to go up the nearby hilltop where he would find flowers aplenty, even though it was winter. He found Castilian roses and gathered many and placed them in his tilma, a long cloak used by Mexican Indians. He came back to the Virgin, who rearranged them and commanded him to go to the Bishop without opening it until he was in the Prelate’s presence.

After a long wait and much difficulty getting past the servants of the palace, Juan Diego finally stood before the Bishop. He unfolded his tilma, and the roses fell out. The Bishop and his attendants fell on his knees before him, for a life-size figure of the Holy Virgin was printed on the poor tilma of Juan Diego. It was December 12, 1531.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

There are many aspects of these apparitions that have often been the subject of commentaries: that Our Lady chooses simple and pure souls to speak to mankind, that she is pleased to appear to humble peasants, that she challenges the human respect of her emissaries, etc. I think that these are good points, but they have already been stressed

An aspect that receives less attention that I believe is very interesting is the attitude of the Indian Juan Diego before Our Lady and the language he used to address her. His manner and language have an extraordinary tonus that corresponds to Our Lady’s attitude toward him from the beginning of the apparition. Our Lady treated him as a dearly loved son, with an extraordinary kindness, as if he were a child.

There is a marvelous contrast we can see in the general conduct of Our Lady. On one hand, there is the love she has for great souls, the heroic souls who accomplish great things in the lives of peoples and civilizations; on the other hand there is the love she has for small, simple souls entirely turned toward her and forgetful of their own virtue. It is marvelous to see how she speaks to these small souls with love and a particularly touching tenderness.

The attitude of Juan Diego is also interesting. He is a simple man, without any education, but in his simplicity he addresses Our Lady as a truly courteous man. He greets her, he inquires about her well being, he describes how he executed the mission he received as if he were a real diplomat, and he explains to Our Lady the practical cause for his failure.

He had presented himself in the Bishop’s palace to transmit the message of Our Lady and was treated disdainfully by the servants and valets of the palace. So he reasoned thus: If I were a noble and powerful man, I would be well received and my message would have more credibility.

He thought he was doing a good thing by giving this counsel to Our Lady: You should choose someone important to deliver your message; then the Bishop will receive him well and everything will go as you have asked. One sees in him the humble desire to not appear or shine and also, to a certain measure, his desire to avoid trouble. So in his charming simplicity he gave her that advice.

There are many qualities in this response, but here I want to stress his tact. He gives her a fine diplomatic counsel to resolve the situation. He also closes his suggestion in a courteous way: My Lady, I beg you not to be displeased with me. It was not my intention to anger or irritate you.

That is to say, he found a good way to excuse himself while presenting his suggestion. He is a simple peasant, but we can see a certain nobility in this attitude. One can also see that Our Lady liked the way he presented his idea. She probably smiled kindly at his diplomatic advice, but she did not accept it. On the contrary, she asked that he return to speak with the Bishop.

It seems that Juan Diego was willing, but found that he needed to postpone the task. His uncle was sick and seemed close to death, so he went to find a priest for him. He thought that Our Lady could wait until the next day. But she caught him on the different route he took to avoid her. Then she not only cured his uncle, but worked the miracle the Bishop had demanded. So finally, with that miracle, the apparition of Our Lady was approved by the Bishop.

There is a lesson for us in this episode: Wherever true virtue exists, courtesy and noble manners develop as a consequence of it. The opposite is also true: When virtue is no longer present, courtesy and nobility of manners disappear. Juan Diego was from a very simple social level; notwithstanding, he acted as a noble when he dealt with Our Lady.

The Catholic courtesy that bloomed in Europe was, at base, a daughter of the virtue that society practiced in the Middle Ages. When this virtue died away and the Revolution started to be accepted by society, courtesy lost its root and began to move toward the complete brutality of manners that exists in Communist countries or the blatant vulgarity that prevails in the Western countries that adhered to egalitarianism.

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

St. Juan Diego - 9th December 2008

Juan received an early education according to the pre-Hispanic traditions, including the knowledge of “the one true God for whom one lives.” Later he married his wife, Malintzin, and they had children. He was a landowner, a small farmer and was involved in textile manufacturing. He had a good deal of property, some he inherited, and the rest came from his mat making business. He made mats from the reeds growing along the shores of Lake Texcoco.

Juan lived in Mexico before and after the Spanish Conquest of 1521 and before the establishment of Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent English colony, in 1607. The Conquest was an apocalyptic event for the indigenous peoples. They lost their freedom, their land, their religion, their culture, their society and their great city of Tenochtitlan. Juan’s life bridged two cultures from the pre-Conquest worship of false gods and the human sacrifices made to appease them to the post-Conquest worship of the One True God and the end of human sacrifice.

After the Conquest, Juan converted to Christianity between 1524-25 and was baptized, together with his wife by the Franciscan missionary, Fray Toribio de Benavente whom the Indians called “Motolinia” or “the poor one”. He was baptized as Juan Diego (John) and she was baptized as Maria Lucia (Mary). In 1524 they celebrated the sacrament of Matrimony. Shortly later, they heard a sermon regarding how the virtue of chastity is pleasing to God. By mutual consent they decided to live their marriage thereafter as celibates, until Maria Lucia’s death in 1529. After that, Juan lived with his uncle, Juan Bernardino, in the village of Tolpetlac, located nine miles from Tlaltelolco where they attended Mass.

Ten years after the Conquest on Saturday, December 9, 1531, 57-year-old Juan, a recent widower, began his nine-mile walk from his home in Tolpetlac probably to Tlaltelolco near Mexico City “in pursuit of God and His commandments”, according to the Nican Mopohua, the earliest account of the apparitions written in 1545. Juan was walking to attend Mass and catechetical instructions.

Then, from the top of the hill, he heard a sweet feminine voice affectionately call him by name, “Juan, dearest Juan Diego.” He quickly climbed to the top of the hill to see who was there. He saw a beautiful young lady. Her dress shone like the sun and transformed the appearance of the rocks and plants on the barren cactus hill into glittering jewels. The ground glistened like the rays of a rainbow in a dense fog.

She identified herself to him as “the perfect and perpetual Virgin Mary, Mother of the one true God for whom one lives . . . .” She entrusted a mission to him to request Bishop Zumarraga to build a church on the hill so that she could manifest her Son to all of the people. She said, “I ardently desire that a little sacred house be built here for me where I will manifest Him, I will exalt Him, I will give Him to the people through my personal love, through my compassionate gaze, through my help and through my protection. Because I am, in truth, your merciful Mother and the mother of all who live united in this land and of all mankind, of all those who love me, of those who cry to me, of those who have confidence in me. Here I will hear their weeping and their sadness and will remedy and alleviate their troubles, their miseries and their suffering.”

(The rest of this Story will continue on the Feat of Our Lady Of Guadalupe on the 12th December 2008)

Juan Diego is a saint not because Our Lady appeared to him, but because he exercised heroic virtues. In his beatification address, Pope John Paul II praised Juan’s virtues, “his simple faith, nourished by catechesis and open to the mysteries; his hope and trust in God and in the Virgin; his love, his moral coherence, his unselfishness and evangelical poverty.

"Living the life of a hermit here near Tepeyac, he was a model of humility. The Virgin chose him from among the most humble as the one to receive that loving and gracious manifestation of hers which is the Guadalupe apparition. Her maternal face and her blessed image which she left us as a priceless gift is a permanent remembrance of this. In this manner she wanted to remain among you as a sign of the communion and unity of all those who were to live together in this land. . . .”

Juan exhibited the Marian virtues of humility, obedience, charity, trust, patience, poverty and chastity.

Like Mary, who saw herself as the lowly handmaid of the Lord, Juan saw himself as a nobody. Like Mary, who obeyed and accepted to be a mother to carry Christ, Juan obeyed and accepted to be carrier of the message of Mary. Like Mary, who in charity cared for her elderly pregnant cousin Elizabeth, Juan cared for his elderly dying uncle, Juan Bernardino. Like Mary, who “trusted that the Lord’s promise to her would be fulfilled” (Lk. 1:45), Juan trusted Our Lady’s promise that the Bishop would recognize her will and fulfill it through the sign of the roses. Like Mary, who patiently waited for nine months for the Lord’s promise to be fulfilled, Juan patiently waited for days for Our Lady’s promise to be fulfilled. Like Mary, who lived in poverty and chastity as a widow, Juan, the widower, gave up his possessions and lived in poverty and chastity until his death. Finally, like Mary, Juan didn’t argue with God’s will, he didn’t complain and he didn’t doubt. He simply did as he was asked, endured the derision of the Bishop’s servants and persevered in fortitude, as did Mary who endured the derision of her detractors who accused her of adultery.

At Juan’s canonization Mass, Pope John Paul II said, “With deep joy I have come on pilgrimage to this Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Marian heart of Mexico and of America, to proclaim the holiness of Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, the simple, humble Indian who contemplated the sweet and serene face of Our Lady of Tepeyac, . . . . Blessed Juan Diego, a good, Christian Indian, whom simple people have always considered a saint! …

“In this new saint you have a marvelous example of a just and upright man, a loyal son of the Church, docile to his Pastors, who deeply loved the Virgin and was a faithful disciple of Jesus.”

Before his final blessing, the Holy Father said, “You have now in your new saint a remarkable example of holiness. . . . May he be a model for you and others that you may also be holy.”

Juan’s mission resulted in the largest mass evangelization in the history of the world. Nine million indigenous peoples of Mexico were converted to the one true God in nine years, the practice of human sacrifice ended in Mexico and the indigenous peoples were reconciled to their Spanish conquerors, intermarried with them and formed the new Mexican race.

During his homily at Juan’s canonization Mass, Pope John Paul II remarked on the formation of the Mexican people and said, “In accepting the Christian message without forgoing his indigenous identity, Juan Diego discovered the profound truth of the new humanity, in which all are called to be children of God. Thus he facilitated the fruitful meeting of two worlds and became the catalyst for the new Mexican identity, closely united to Our Lady of Guadalupe, whose mestizo face expresses her spiritual motherhood that embraces all Mexicans.”

Monday, December 8, 2008

The Immaculate Conception and the enemies of the Catholic Church

One of the truly Counter-Revolutionary acts of Pope Pius IX’s pontificate was the proclamation of the Immaculate Conception.

There are three reasons the definition of this dogma was especially Counter-Revolutionary and therefore hateful to the enemies of the Church.

First Reason:An Anti-Egalitarian Dogma

As you know, this dogma teaches that Our Lady was immaculate at her conception, meaning that, at no moment, did she have even the slightest stain of Original Sin. Both she, and naturally Our Lord Jesus Christ, were exempt from that rigid law that subjugates all other descendants of Adam and Eve.

Thus, Our Lady was not subject to the miseries of fallen man. She did not have bad influences, inclinations and tendencies. In her, everything moved harmonically towards truth, goodness and therefore God. In this sense, Our Lady is an example of perfect liberty, meaning that everything her reason, illuminated by Faith, determined as good, her will desired entirely. She had no interior obstacles to impede her practice of virtue.

Being “full of grace” increased these effects. Thus, her will advanced with an unimaginable impetus towards everything that was true and good.

Declaring that a mere human creature had this extraordinary privilege makes this dogma fundamentally anti-egalitarian, because it points out an enormous inequality in the work of God. It demonstrates the total superiority of Our Lady over all other beings. Thus, its proclamation made Revolutionary egalitarian spirits boil with hatred.

Second Reason:The Unsullied Purity of Our Lady

However, there is a more profound reason why the Revolution hates this dogma.

The Revolution loves evil and is in harmony with those who are bad, and thus tries to find evil in everything. On the contrary, those who are irreproachable are a cause of intense hatred. Therefore, the idea that a being could be utterly spotless from the first moment of her existence is abhorrent to Revolutionaries.

For example: Imagine a man who is consumed with impurity. When besieged by impure inclinations, he is ashamed of his consent to them. This leaves him depressed and utterly devastated.

Imagine this man considering Our Lady, who, being the personification of transcendental purity, did not have even the least appetite for lust. He feels hatred and scorn because her virtue smashes his pride.

Furthermore, by declaring Our Lady to be so free from pride, sensuality and the desire for anything Revolutionary, the proclamation of the Immaculate Conception affirmed that she was utterly Counter-Revolutionary. This only inflamed the Revolutionary hatred of the dogma all the more.

Disputing the Doctrine:A Counter-Revolutionary Struggle

For centuries, there were two opposing currents of thought about the Immaculate Conception in the Church. While it would be an exaggeration to suggest that everyone who fought against the doctrine was acting with Revolutionary intentions; it is a fact that all those who were acting with Revolutionary intentions fought against it. On the other hand, all those who favored its proclamation, at least on that point, expressed a Counter-Revolutionary attitude.

Thus, in some way the fight between the Revolution and Counter-Revolution was present in the fight between these two theological currents.

Third Reason:The Exercise of Papal Infallibility

There is still another reason this dogma is hateful to Revolutionaries: it was the first dogma proclaimed through Papal Infallibility.

At that time, the dogma of Papal Infallibility had not yet been defined and there was a current in the Church maintaining that the Pope was only infallible when presiding over a council. Nevertheless, Pius IX invoked Papal Infallibility when he defined the Immaculate Conception after merely consulting some theologians and bishops.

For liberal theologians, this seemed like circular reasoning. If his infallibility had not been defined, how could he use it? On the contrary, by using his infallibility, he affirmed that he had it.

This daring affirmation provoked an explosion of indignation among Revolutionaries, but enormous enthusiasm among Counter-Revolutionaries. In praise of the new dogma, children all over the world were baptized under the name: Conception, Concepcion or Concepta to consecrate them to the Immaculate Conception of Our Lady.

Pius IX:Bringing the Fight to the Enemy

It is not surprising that Pius IX so adamantly affirmed Papal Infallibility. Very different from those who succeeded him, he was ever ready to bring the fight to the enemy. He did this in Geneva, Switzerland, which then was the breeding ground of Calvinism, which is the most radical form of Protestantism.

When Swiss laws changed to allow a Catholic Cathedral in Geneva, Pius IX ordered that a statue of the Immaculate Conception be placed in the middle of the city, to proclaim this dogma in the place where Calvinists, Lutherans and other Protestants denied it more than anywhere else. This is an example of Pius IX’s leadership in the fight against the Revolution.

It is therefore entirely proper that all Catholics entertain a special affection for the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, which is so detested by the enemies of the Church today.

Wednesday, December 3, 2008

St. Francis Xaviers - 3rd December 2008

Today we celebrate the feast of St. Francis Xavier. He is the patron saint of our family. This is because we studied in St. Xavier's in Mumbai named after this great saint. Let us read the commentary that Dr. Plino has written about this Jesuit Saint.

Biographical selection:

St. Francis Xavier (1506-1552), born of a noble Spanish family, Jesuit missionary and confessor, Apostle to the Far East and special patron saint of the Missions.

The biography of St. Francis Xavier by Daurignac reprints a section of a letter he wrote to Dom John III, King of Portugal:

“My Lord, Your Highness should fear the moment when God will call you to stand before Him, which will happen without fail and perhaps when you least expect it. You should fear, great Prince, that an irate Judge will address you with these terrible words of accusation:

‘Why have you not proceeded with rigor against your ministers and subordinates who plotted against Me in India and did not fear to declare themselves in rebellion against Me? Why was your severity lax except when they failed to pay their taxes or were negligent in the administration of your finances?’

“My Lord, then you will answer God with the following excuse of little value:

‘For Thy glory I wrote to those countries every year recommending the greatest zeal in working for Thee and obeying Thy precepts.’

“Then the Lord will say to you:

‘Yes, you did so, but you did not punish all those who were indifferent to those orders.’”

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

It is a very beautiful text. You should consider that at that time the King of Portugal had important lands in India. In an annual letter to his subordinates, he recommended that they do everything possible to promote the Catholic Faith.

However, St. Francis Xavier, who was there making his apostolate, witnessed that those orders were not followed and that those officials even plotted to prevent the Catholic Faith from expanding. They were decadent men, probably linked to some sort of Masonry that was already secretly acting against the designs of the King of Portugal to sabotage the spread of the Catholic Faith.

St. Francis Xavier wrote to the King, giving him this warning: It is not enough to send orders; it is necessary to punish those who disobey you, because a command unaccompanied by punishment of those who flout it is a futile thing without value. It will not stand before God as the accomplishment of your duty.

He told him: You, the King, have the obligation to punish those who violate your orders to uphold and spread the Faith as strongly as you punished those who did not pay their taxes to the Crown. If you punished them for the taxes and not for religion, it means that you consider taxes more valuable than the Catholic Faith.

Then, the Saint warned the King: You should be aware that God may call you at any moment and then you will not be able to escape His judgment.

Indeed, at any moment he could have an accident, an attempt against his life could be made, he could become gravely ill, or some other such thing could bring him before the tribunal of God. Then, how would the King respond to God regarding the use of his power?

St. Francis Xavier reminded him of two principles: first, the temporal power’s principal concern should be to expand the Catholic Faith rather than increase the royal fortune; second, the exercise of his power should be accompanied with the threat of punishment for those who disobey his orders. The King will have to answer to God for that.

It is admirable to see the liberty with which St. Francis Xavier addressed one of the powerful men of the time. In times past, when someone used this kind of frankness, it was termed in ecclesiastical language “apostolic frankness.” It is a beautiful expression that reveals the courage an apostle must have. He is a representative of God and must use the language of God. Therefore he has the right to say the most unpleasant things to the most powerful men, and he has the right to be heard.

St. Francis Xavier spoke to the King, realizing the serious possibility that his words might change the King’s way of acting. In any circumstance, he fulfilled his duty and the warning was given. From that moment on, the King had to answer for his actions in that matter before God.

You see how this behavior is logical, noble, and beautiful. But you also see that today it seems outdated. Not because such behavior became obsolete in itself, but rather because men became so decadent and lax that they no longer want to hear such words. For this reason, today’s progressivist Catholics would accuse St. Francis Xavier of lacking charity for speaking in this way. They would say that this kind of admonition showed that he was lacking in the Catholic spirit.

People who say this are wrong, because here we have the words of one of the greatest saints of the Catholic Church, St. Francis Xavier, who spoke this way. The saints did not use the honeyed language of this false ecumenism that is everywhere in today’s Church.

This text of St. Francis Xavier is a confirmation that our anti-progressivist position is correct. The words of the true Catholic apostle should be like his. We should pray to him and to Our Lady that, until we die, we always have the courage to use this language.

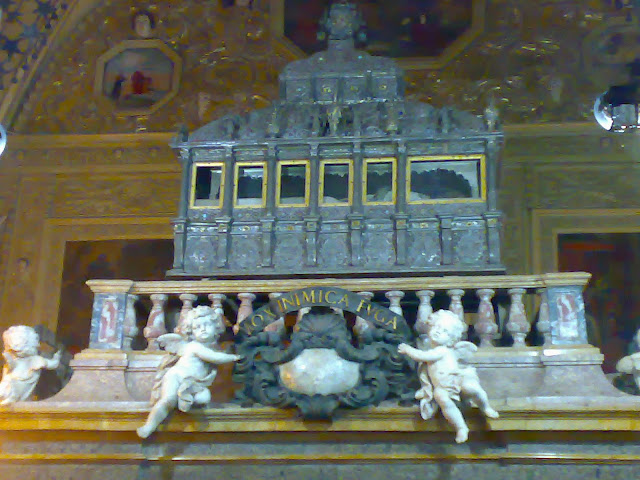

(The body of St Francis Xavier in Goa, India)

(The body of St Francis Xavier in Goa, India)

Tuesday, December 2, 2008

Been Busy

I have been busy. Busy preparing for a little spiritual holiday a retreat in a way. My only sibling is going to be ordained in a nice South American country. It will be the first time that my parents, my wife and my sibling will be in the same country at the same time, an occasion which has not happened for over at least 7 or 8 years.

We shall all attend his ordination and then spend Christmas together and then once he is ordained he will say a special mass for our wedding aniversary. All in all I am a happy about all of this.

And yet I worry, the recent terrorist attacks in Mumbai and the growing tension between India and Pakistan might spill into a war which might prevent my parents from traveling. So do keep us in your prayers that we all have a safe journey.

And I shall put up some pictures on my return.

Wednesday, November 26, 2008

St. Leonard of Port Maurice - 26 November 2008

Saint Leonard of Port Maurice was the Son of Domenico Casanova, a sea captain, and Anna Maria Benza. Placed at age thirteen with his uncle Agostino to study for a career as a physician, but the youth decided against medicine, and his uncle disowned him. Studied at the Jesuit College in Rome. Joined the Riformella, a branch of the Franciscans of the Strict Observance on 2 October 1697, taking the name Brother Leonard. Ordained in Rome in 1703. Taught for a while, and expected to become a missionary to China, but a bleeding ulcer kept him in his native lands for the several years it took to recover and regain his strength.

Sent to Florence in 1709 where he preached in the city are nearby region. A great preacher, he was often invited to other areas. Worked for devotion to the Blessed Sacrament, Sacred Heart, Immaculate Conception, and the Stations of the Cross. Established the Way of the Cross in over 500 places, including the Colosseum. Sent as a missionary by Pope Benedict XIV to Corsica in 1744. He restored discipline to the holy orders there, but local politics greatly limited his success in preaching. He returned exhausted to Rome where he spent the rest of his days.

It is very profitable for the soul that all Catholics read this sermon of the saint 'The little Number of Those who are saved'

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

Thoughts on family

Lately, I have been worried that my orthodox views will get me and my family in trouble. More particularly that i would be killed or jailed and that my family would suffer. While roaming around on the blogs i noticed that many Catholic men had this same worry. Then last night as I was stepping out of the bathtub and wiping myself dry something hit me. A scripture verse to be precise. 'If anyone puts family of friends before me he is not worth to enter the Kingdom of God' BANG like a bolt from the blue. All my worries about what would happen to my family vanished. I thought about it more, if I did not put God first then I would be really losing my family, but if I did put God first, it would appear that I would be losing my family for now but in the end when it mattered I would gain family. This corresponds with another bible verse ' He who loses his life for my sake gains it and He who tries to save his life will lose it'. My life to me is my family. Thus i think God is asking me to put Him first above even Family. After all he gave me the gift of life and family and He has the right to take it away if He so chooses.

St. Catherine of Alexandria – 25 November 2008

Biographical Section

After the unsuccessful attempt to kill St. Catherine on the wheel, Emperor Maxentius ordered her to be beheaded. She was conducted to the place of her martyrdom followed by a multitude, mainly ladies of high condition who wept at her fate. The virgin walked with a great calm. Before dying she said this prayer:

“Lord Jesus Christ, my God, I thank Thee for having firmly set my feet on the rock of the Faith and directed my steps on the pathway of salvation. Open now Thy arms wounded on the cross to receive my soul, which I offer in sacrifice to the glory of Thy Name.

“Forgive the faults I committed in ignorance and wash my soul in the blood I will shed for Thee. Do not leave my body, slaughtered by love for Thee, in the power of those who hate me. Kindly regard this people and give them the knowledge of the truth. Finally, O Lord, in Thy infinite mercy exalt those who will invoke Thee through me so that Thy name be always glorified.”

After saying these words, she told the soldiers to execute their orders, and she was beheaded with but one blow of the sword. It was November 25 (around the year 310).

Soon numerous miracles began to take place. Her body, as she had asked, was carried away by Angels and buried on Mount Sinai so that she might rest where God had written on stone His law, which she had so faithfully kept written on her heart.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

This excerpt from the life of St. Catherine of Alexandria is so elevated that I lament commenting on it. It would be better to leave it shining alone on the horizon. But since I am asked to analyze it, I will say some words.

The first thing that occurs to me is the good position of the ladies of high society of those times. Today, such ladies often form a network that slanders and disparages the good cause. What a great potential there was in that country, where the ladies of high condition followed St. Catherine to the place of martyrdom, weeping for her, sympathetic for her, a martyr whose life would be snuffed out by the Emperor’s hatred. The Emperor was omnipotent; he could condemn any of them to death; notwithstanding they were there with St. Catherine.

It is beautiful to see the contrast of spirits in the picture and the different graces the Holy Ghost was giving. The ladies were weeping, probably touched by the gift of tears. But St. Catherine did not weep, she was calm, serene, and walked unswervingly toward death, inundated by another kind of grace of the Holy Ghost. She did not weep over her own situation, that martyrdom which grace moved the others to lament. One can imagine how impressive it was to see that cortège of ladies walking between aisles of soldiers and then to find that the only one who was serene, counseling the others to be tranquil, was St. Catherine, who was shortly to die.

Then, before her life ended, she said a prayer. It has the beauty of shining lights that fill the skies and emanate from many places. They do not come from just one source, from one central idea.

So, she began: “Lord Jesus Christ, my God.” Even as the Emperor tried to oblige her to adore the idols, she affirmed the divinity of Our Lord to show that she did not recognize any other god but Him.

The next thing she said, “I thank Thee for having firmly set my feet on the rock of the Faith and directed my steps on the pathway of salvation.” That is to say: I thank You for making me belong to You, the source of my salvation. You are the origin of every good that exists in me. I am good because You are good and gave me the solidity of the Catholic Faith; You made me love virtue and gave me the firmness to practice it. I recognize that everything that exists in me came from You.

She continued: “Open now Thy arms wounded on the cross to receive my soul, which I offer in sacrifice to the glory of Thy Name.” Nothing more beautiful can exist! She asked her Crucified Lord to open His bloodied arms to receive her soul as she left this life, which also saw its earth soaked with the blood of her martyrdom. What a marvelous intimacy! What an encounter: the Martyr of martyrs Our Lord Jesus Christ and this heroic and grandiose martyr St. Catherine of Alexandria! What a magnificent thought, that her blood should intermingle with the blood of Our Lord! What a profound idea of the communion of saints is expressed in such a desire! She had such a great certainty that she would be received into Heaven that she asked Our Lord to embrace her. How admirable such certainty is!

Then she said: “Forgive the faults I committed in ignorance and wash my soul in the blood I will shed for Thee.” She was afraid that she had committed some faults, and she asked to be washed clean by the merit of her martyrdom.

“Do not leave my body, slaughtered by love for Thee, in the power of those who hate me.” After having asked Our Lord to attend to her soul, she asked refuge for her body. You can see the respect she had for her own body, for the sanctity of the body that was her companion in the practice of virtue. And what a magnificent response to this request! Soon after she died, the Angels came and transported her body to the most majestic mountain that exists on earth after Mount Calvary, which is Mount Sinai, where God gave His Law to men.

“Kindly regard this people and give them the knowledge of the truth.” She was no longer thinking of herself, but of the ones she was leaving behind.

“Finally, O Lord, in Thy infinite mercy, exalt those who will invoke Thee through me, in order that Thy name be always glorified.” She was so certain that she would go to Heaven that she was already interceding for those who would pray to her.

Once this prayer was said, she calmly told the soldiers to carry out her sentence. No trembling, no desire to prolong her life a little more. Also, no precipitation, which sometimes is a reflection of fear. No. She said everything she wanted to say, and when she finished, she delivered herself into the hands of God. The soldiers beheaded her, and immediately afterward, her prayer started to be answered.

What grace should we ask of St. Catherine of Alexandria? We should ask her that when the chastisement predicted in Fatima will be realized and we face the enemies of the Church and Christendom, that we have the same serenity she had in face of death. It is a serenity that only grace can give. In face of death, there are two kinds of serenity: one is the serenity of the idiot, another is the serenity that comes from grace. Death, the separation of the body and soul, the apparent plunging into nothingness, is such a terrible thing that only two kinds of serenity are comprehensible: that of the idiot who never measures the consequences of anything, or the serenity of the man inundated by grace.

So then, let us ask St. Catherine to help us be calm in every situation in our lives, and especially in the risks and dangers of life, and even in the extreme sacrifice of death, if that should be the will of Our Lady for us.

Monday, November 24, 2008

St. Andrew Dung-Lac and Companions - 24th November 2008

St. Andrew was one of 117 martyrs who met death in Vietnam between 1820 and 1862. Members of this group were beatified on four different occasions between 1900 and 1951. Now all have been canonized by Pope John Paul II.

Christianity came to Vietnam (then three separate kingdoms) through the Portuguese. Jesuits opened the first permanent mission at Da Nang in 1615. They ministered to Japanese Catholics who had been driven from Japan.

The king of one of the kingdoms banned all foreign missionaries and tried to make all Vietnamese apostatize by trampling on a crucifix. Like the priest-holes in Ireland during English persecution, many hiding places were offered in homes of the faithful.

Severe persecutions were again launched three times in the 19th century. During the six decades after 1820, between 100,000 and 300,000 Catholics were killed or subjected to great hardship. Foreign missionaries martyred in the first wave included priests of the Paris Mission Society, and Spanish Dominican priests and tertiaries.

Persecution broke out again in 1847 when the emperor suspected foreign missionaries and Vietnamese Christians of sympathizing with the rebellion of one of his sons.

The last of the martyrs were 17 laypersons, one of them a 9-year-old, executed in 1862. That year a treaty with France guaranteed religious freedom to Catholics, but it did not stop all persecution.

By 1954 there were over a million and a half Catholics—about seven percent of the population—in the north. Buddhists represented about 60 percent. Persistent persecution forced some 670,000 Catholics to abandon lands, homes and possessions and flee to the south. In 1964, there were still 833,000 Catholics in the north, but many were in prison. In the south, Catholics were enjoying the first decade of religious freedom in centuries, their numbers swelled by refugees.

During the Vietnamese war, Catholics again suffered in the north, and again moved to the south in great numbers. Now the whole country is under Communist rule.

Sunday, November 23, 2008

Bl. Miguel Pro

Here is a comparatively rare event in the history of the Church: a camera is witness to a martyrdom. The whole affair was orchestrated in 1927 by a fierce enemy of the Church whose savage blows only served to strengthen and glorify both her and the individual victims of his wrath.

Here is a comparatively rare event in the history of the Church: a camera is witness to a martyrdom. The whole affair was orchestrated in 1927 by a fierce enemy of the Church whose savage blows only served to strengthen and glorify both her and the individual victims of his wrath.A sketch of Bl. Miguel Pro's life brings to mind the story of his spiritual forbears, the martyr-priests in post-Reformation England. Like them, he lived at a time when his nation's leaders turned against the Church. The young Jesuit novice went into exile during the Mexican revolution; like many seminarians during the English persecution, Miguel Pro had to study for the priesthood abroad; he was ordained in Belgium on August 31, 1925. Like his English forbears, Fr. Pro conducted his ministry on the sly, and frequently in disguise.

Fr. Pro was known not only for his devotion and prayerfulness, but also for his wit, his playfulness and his good cheer, especially in the face of a distressing stomach ailment. He was much loved; however, he was eventually betrayed to the authorities and ultimately condemned to death on a trumped-up charge of attempting to assassinate the vice-president.

On the day of Fr. Pro's execution by firing squad, the fiercely anti-Catholic president Plutarcho Calles brought the press out to photograph the event, secure in the belief that he would thereby prove that impending death reduced Catholics to sniveling cowards. In the first photograph above, we see Fr. Pro praying, the picture of serenity in the face of the violent death from which he is only moments away. The next photograph shows Fr. Pro confronting the firing squad, sans blindfold, his arms raised in the form of the cross, with a crucifix in one hand and a rosary in the other. Fr. Pro forgave his executioners; and as they took aim, he shouted his last words, "¡Viva Cristo Rey! (Long live Christ the King!)." The firing squad was so shaken by his courage that it succeeded only in wounding him; in the final photograph, a soldier dispatches the fallen priest at point-blank range.

Naturally, these photographs had the opposite effect to that intended; Plutarcho Calles ended up confiscating and outlawing them. And Calles obviously did not succeed in entirely destroying the camera's witness to Fr. Pro's courage, since they survive down to the present day.

(Courtesy[V for Victory!] blog )

Friday, November 21, 2008

The Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary - 21th November 2008

Biographical selection:

The cult to Our Lady was born in the East; from there also we received the feast of the Presentation of Our Lady, where it was celebrated from the end of the seventh century. In the West, Pope Gregory XI adopted the feast day in 1372 at the pontifical court of Avignon.

A year later, King Charles V introduced the feast of the Presentation at the royal Chapel in Paris. In a letter dated November 10, 1374 to the masters and students of the College of Navarre, he expressed his desire that such a feast should be celebrated throughout the kingdom. The text of the letter reads:

'Charles, by the grace of God King of France, to our dearly beloved: health in Him Who ceases not to honor His Mother on earth. '

'Among other objects of our solicitude, daily occupation, and diligent meditation, that which rightly occupies our first thoughts is that the Most Blessed Virgin and Holy Empress be honored by us with very great love, and praised as it is due. For it is our duty to glorify her, and we, who raise the eyes of our soul to her on high, know what a incomparable protectress she is to all, how powerful a mediatrix she is with her Blessed Son for those who honor her with a pure heart .... This is why we wish to stimulate our faithful people to celebrate this feast, as we ourselves intend to do by God's assistance every year of our life. We send to you the liturgy of said feast to increase your joy.' Such was the language of princes in those days. Then also at that very time, that wise and pious King, following up the work begun in Britigny by Our Lady of Chartres, rescued France from its fallen and dismembered condition.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

In other words, the feast of the Presentation of Our Lady followed extraordinary historic circumstances. It was a Pope who introduced it in the West, and the King of France who spread it throughout his country. And from France it extended to the whole world. The King took up the feast to thank Our Lady of Chartres for her protection in the battle of Britigny, where the French army defeated its adversaries.

What does the feast of the Presentation celebrate? It celebrates the fact that the parents of Our Lady brought her to the Temple at the age of three and handed her over to live there for a long period as a virgin consecrated to the Temple, contemplating God exclusively.

What is the special beauty of this feast? Our Lady was the one chosen before time began, the Queen of Jesse from whom the Messiah would be born. The Temple was the only place in the Old Testament where sacrifices were offered to God. It represented, therefore, the only true religion. Our Lady being received at the Temple was the first step to the fulfillment of the promise that the Messiah would come to the true religion. It was the encounter of hope with reality.

When she was received at the Temple, Our Lady entered the service of God. That is, a soul incomparably holy entered the service of God. At that moment, notwithstanding the decadence of the nation of Israel, and even though the Temple had been transformed into a den of Pharisees, the Temple was filled with an incomparable light that was the sanctity of Our Lady.

It was in the Temple atmosphere that, without knowing it, she began to prepare herself to be the Mother of Our Lord Jesus Christ. It was there that she increased her love of God until she formed the ardent desire for the imminent coming of the Messiah. It was there that she asked God the honor to be the maidservant of His Mother. She did not know that she was the one chosen by God. This is so true that she wondered about the meaning of the salutation of the Archangel Gabriel when he greeted her to ask her permission for the Incarnation. That preparation for Our Lady to be the Mother of Jesus Christ began with the Presentation at the Temple, the feast the Church celebrates on November 21.

Is there a grace we should ask on this day? We should ask for spiritual help to be better prepared to serve God as Our Lady did. But the best way to serve God is to serve Our Lady herself. So, on this feast day we should re-present ourselves before Our Lady, asking her to receive our offer of service and to give us her assistance in the task of our sanctification, just as the Holy Ghost helped her at the Temple of Jerusalem.

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

DEDICATION OF THE CHURCHES OF ST PETER AND ST PAUL AT ROME - 18th November 2008

The body of St. Peter is said to have been buried immediately after his martyrdom, upon this spot, on the Vatican hill, which was then without the walls and near the suburb inhabited by the Jews. The remains of this apostle were removed hence into the cemetery of Calixtus, but brought back to the Vatican. Those of St. Paul were deposited on the Ostian Way, where his church now stands. The tombs of the two princes of the apostles, from the beginning, were visited by Christians with extraordinary devotion above those of other martyrs. Caius, the learned and eloquent priest of Rome, in 210, in his dialogue with Proclus the Montanist, speaks thus of them: "I can show you the trophies of the apostles. For, whether you go to the Vatican hill, or to the Ostian road, you will meet with the monuments of them who by their preaching and miracles founded this church."

The Christians, even in the times of persecution, adorned the tombs of the martyrs and the oratories which they erected over them, where they frequently prayed. Constantine the Great, after founding the Lateran Church, built seven other churches at Rome and many more in other parts of Italy. The first of these were the churches of St. Peter on the Vatican hill (where a temple of Apollo and another of Idaea, mother of the gods, before stood) in honour of the place where the prince of the apostles had suffered martyrdom and was buried and that of St. Paul, at his tomb on the Ostian road. The yearly revenues which Constantine granted to all these churches, amounted to seventeen thousand seven hundred and seventy golden pence, which is above thirteen thousand pounds sterling, counting the prices, gold for gold; but, as the value of gold and silver was then much higher than at present, the sum in our money at this day would be much greater. These churches were built by Constantine in so stately and magnificent a manner as to vie with the finest structures in the empire, as appears from the description which Eusebius gives us of the Church of Tyre; for we find that the rest were erected upon the same model, which was consequently of great antiquity. St. Peter's Church on the Vatican, being fallen to decay, it was begun to be rebuilt under Julius II in 1506, and was dedicated by Urban VIII in 1626, on this day; the same on which the dedication of the old church was celebrated The precious remains of many popes, martyrs, and other saints, are deposited partly under the altars of this vast and beautiful church, and partly in a spacious subterraneous church under the other. But the richest treasure of this venerable place consists in the relics of SS. Peter and Paul, which lie in a sumptuous vault beyond the middle of the church, towards the upper end, under a magnificent altar at which only the pope says mass, unless he commissions another to officiate there. This sacred vault is called The confession of St. Peter, or The threshold of the Apostles (

Churches are dedicated only to God, though often under the patronage of some saint; that the faithful may be excited to implore, with united suffrages, the intercession of such a saint, and that churches may be distinguished by bearing different titles. "Neither do we," says St. Austin, "erect churches or appoint priesthoods, sacred rites, and sacrifices to the martyrs; because, not the martyrs, but the God of the martyrs is our God. Who, among the faithful, ever heard a priest standing at the altar which is erected over the body of a martyr to the honour and worship of God say, in praying, We offer up sacrifices to thee, O Peter, or Paul, or Cyprian; when at their memories (or titular altars) it is offered to God, who made them both men and martyrs, and has associated them to his angels in heavenly honour." And again, "We build not churches to martyrs as to gods, but memories as to men departed this life, whose souls live with God. Nor do we erect altars to sacrifice on them to the martyrs, but to the God of the martyrs and our God." Constantine the Great gave proofs of his piety and religion by the foundation of so many magnificent churches, in which he desired that the name of God should be glorified on earth to the end of time. Do we show ours by our awful deportment and devotion in holy places, and by our assiduity in frequenting them? God is everywhere present, and is to be honoured by the homages of our affections in all places. But in those which are sacred to him, in which our most holy mysteries are performed, and in which his faithful servants unite their suffrages, greater is the glory which redounds to him from them, and he is usually more ready to receive our requests—the prayers of many assembled together being a holy violence to his mercy.

(Pope Benedict at the tomb of St. Paul)

Monday, November 17, 2008

St. Elizabeth of Hungary - 17th November 2008

(St. Francis with St. Louis IX (1215-1270), King of France, and St. Elizabeth of Hungary (1207-1231), patrons of the Secular Franciscan Order)

Today we celebrate the feast of St. Elizabeth of Hungary. Let us contemplate what Dr. Plinio has to say about this great saint.

The fame of the virtues of St. Elizabeth [1207-1231] reached Italy where St. Francis of Assisi had founded his order. He came to know about the support and protection the young Duchess of Thuringia had given the Franciscans in Germany and her great love for poverty. Cardinal Ugolini, the future Pope Gregory IX, often spoke of her to Francis.

One day the Cardinal asked St. Francis for a gift for her as a symbol of his recognition. As he made his request, he took the worn cape off St. Francis' shoulders and recommended that he send it to her. 'Since she is filled with your spirit of poverty,' said the Cardinal, 'I would like for you to give her your mantle, just as Elias gave his mantle to Eliseus.' St. Francis obeyed and sent his mantle to St. Elizabeth, whom he considered as a daughter.

She always kept it with her, and wore it while praying whenever she desired to obtain a special spiritual grace. Later, after she had lost everything, she still conserved the precious mantle of her spiritual father until her death.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

This incident is rich in teachings for us.

St. Francis of Assisi followed the advice of Cardinal Ugolino, the future Pope Gregory IX, and imitated the example of Elias with Eliseus. He gave his mantle to St. Elizabeth, and when she prayed she used to wear it to be more pleasing to God. She had the certainty that the mantle St. Francis had worn was a symbol of his alliance with her, a symbol of the union of the two souls, and, therefore, a symbol that would draw from God the same graces that St. Francis attracted.

Underlying this incident is a theory about symbols like this.

Rebecca advised her son Jacob to wear a goat skin and approach his blind father Isaac so that he would seem like Esau and receive the blessing due the first born. This covering made Jacob pleasing to his father because he was vested in a way that gave the impression he was the first born. In this episode we have the affirmation of a principle according to which, in certain circumstances, a person who takes on the appearance of another can receive from God the privileges due to the other person.

Something similar happened with Eliseus. By putting on the mantle of Elias, he earned the privilege of being treated by God as if he were Elias. He was the perfect disciple of Elias, the favorite of Elias, he was a kind of extension of the personality of Elias. The mantle Elias gave to Eliseus was a symbol of this union of spirit.

Likewise, in a manner infinitely higher, we have Our Lord Jesus Christ, Who took on human flesh, suffered the Passion and the Crucifixion for us, and washed our sins with His Blood. The merit of His Blood covers us, as the mantle of Elias covered Eliseus. With this red mantle we can present ourselves before God Who is thus pleased to receive us, forgive us, and give us the graces necessary for repentance and the amendment of our lives. We are able to appear before God because we are clothed in the mantle of the innocence and the suffering of Christ and with this, we take on His appearance.

Something like this takes place with Our Lady. She takes the initiative of covering us with her mantle. Then she says to God: 'I vest these children with my merits as their mother, and I want You to consider them as my children.' So, Our Lord looking at us, sees extensions of the personality of Our Lady, and becomes pleased, forgives us, and tries to help us.

In all these episodes 'Jacob and Isaac, Eliseus and Elias, St. Elizabeth and St. Francis, Our Lady with us, and us with Our Lord ' there is some special union of souls that allows one soul to be clothed with the merits of another in order to appear before the Throne of God and be pleasing to Him.

We can apply this principle to our lives. We should have confidence and not despair in face of our weaknesses and guilt. One of us can approach God and say: 'Do not look at my sins, but see instead the merits of your Son and the intercession of Our Lady.'

We should have the honesty to see our defects and sins, because this is what we are supposed to do, but we should not despair, since even if our sins are great we can present ourselves before God vested in the merits of Our Lady and Our Lord. We should have confidence that this marvelous chain of substitutions will be accepted with pleasure by the infinite mercy of God.

Sunday, November 16, 2008

St. Albert the Great - 15th November 2008

Albert the Great, the eldest son of the Count of Bollstadt, was born around 1206 in Lauingen, in Swabia, Germany. After a careful formation he went to study Law at the University of Padua in Italy. There he became familiar with Blessed Jordan of Saxony, General of the Dominicans, whose counsels led him to enter the Dominican Order. Soon he became known for his filial devotion to Our Lady and attention to monastic observance. He was sent to Cologne to finish his studies, earning a reputation for an erudition in the natural sciences greater than all his peers.

After completing his studies, he was sent to teach theology at Hildesheim, Freiburg-im-Breisgau, Regensburg, Strasburg and Cologne. In 1245, he was sent to the University of Paris, where he demonstrated the accord between faith and reason and between the sacred and profane sciences. The most illustrious of his disciples, St. Thomas Aquinas, would succeed him at the Sorbonne.

St. Albert retuned to Cologne in 1248 in order to direct the studies of his Order as Regent of the Studium Generale. In 1254 he was elected Dominican provincial of Germany, and in 1260 was appointed Bishop of Regensburg. He resigned the bishopric after three years, and returned to teach at Cologne.

Often, he was also called to act as arbiter and peacemaker between various German Princes and Bishops. He attended the second Council of Lyons (1274), where he took an active part in the deliberations. He died in Cologne on November 15, 1280. On December 16, 1931 he was canonized and declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XI.

Since the year 1300, under a stain-glass window in the Dominican church of St. Andreas in Cologne, one can read these words:

'This sanctuary was built by Bishop Albert, flower of philosophers and wise men, model of good customs, brilliant and splendorous destroyer of heresies, and scourge of evil men. Place him, O Lord, in the number of Thy Saints.'

"By nature he had an instinct for great things. Thus, like Solomon, he begged God for the gift of wisdom, which intimately unites man to God, expands hearts, and raises the souls of the faithful to the heights. Wisdom taught him how to unite an intensive intellectual life with a profound spiritual life, for he was at the same time an initiator of a powerful intellectual movement, a great contemplative, and a man of action"

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

The life of St. Albert the Great is expressed well in the description of how he excelled in these three things he was an intellectual, a contemplative and a man of action. This made him one of the greatest figures of the Middle Ages, one of those who consolidated the Middle Ages.

God gave him the gift to be remarkable in many things. Had he shone in only one of these things, he would be a man of immortal fame. To mention just two of his intellectual accomplishments, St. Albert is considered the founder of Scholasticism, and he was the master of St. Thomas Aquinas, who in his turn brought Scholasticism to its apex. If he were only this great intellectual, he would have gone down in history for this. But he was more. He was also renowned for his religious spirit, he was a great contemplative, a great saint, which would give him all possible glory. Finally, he was also an illustrious Bishop who acquired an enormous fame in his homeland.

Why does Providence make such a brilliant man, who stands out on three different roads at the same time? It is to show that the interior life should have precedence over the others. We understand that if St. Albert had not been a man with a strong interior life, he could not have been the extraordinary scholar that he was. The interior life gives the means for a man to execute God's will for him to perfection. Doing this, a man fully develops his natural talents. Often God gives additional charismas and extraordinary graces to those who are faithful in order to multiply their natural qualities and help them accomplish their missions.

This reminds me of a saying of Dom Chautard, the author of the famous book The Soul of the Apostolate. Once he was with Georges Clemenceau, the very revolutionary French prime-minister. Knowing that Dom Chautard was a very busy man, Clemenceau asked him: 'How do you manage to do so many things in just 24 hours?' Dom Chautard answered, 'It is because I pray the Rosary. If you would also pray it, you would find more time to accomplish your tasks.'

It is a paradox, because to pray the Rosary takes time from other activities. Someone might think that Dom Chautard was just joking with Clemenceau. This is not true. In that apparent contradiction there is a profound truth. If we take time to develop our interior life, God will take care of the other things we need, and will multiply our capacity to accomplish what we are called to do.

This is the great truth that we learn from St. Albert's life.

Those beautiful words written in 1300 under that stain-glass window in St. Andreas Church reveal how much the modern religious mentality has changed. Today, who would say that a saint is a 'brilliant and splendorous destroyer of heresies and scourge of evil men'? Such a eulogy ' which fills our souls with Catholic joy ' has completely disappeared from the present day religious panorama. That this is so reveals the difference between the mentality of the Progressivism that unfortunately dominates the Church today and the true Catholic spirit. It is not difficult to see which one is the position of the Saints.

Let us ask St. Albert the Great to help us to see the full extension of the progressivist errors and combat them with the same brilliancy and splendor that he combated the heresies of his time.

Thursday, November 13, 2008

SAINT FRANCES XAVIER CABRINI - 13th November 2008

Mother Cabrini was the foundress of the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart and pioneer worker for the welfare of dispersed Italian nationals, this diminutive nun was responsible for the establishment of nearly seventy orphanages, schools, and hospitals, scattered over eight countries in Europe, North, South, and Central America.

Francesca Cabrini was born on July 15, 1850, in the village of Sant' Angelo, on the outskirts of Lodi, about twenty miles from Milan, in the pleasant, fertile Lombardy plain. She was the thirteenth child of a farmer's family, her father Agostino being the proprietor of a modest estate. The home into which she was born was a comfortable, attractive place for children, with its flowering vines, its gardens, and animals; but its serenity and security was in strong contrast with the confusion of the times. Italy had succeeded in throwing off the Austrian yoke and was moving towards unity. Agostino and his wife Stella were conservative people who took no part in the political upheavals around them, although some of their relatives were deeply concerned in the struggle, and one, Agostino Depretis, later became prime minister. Sturdy and pious, the Cabrinis were devoted to their home, their children, and their Church. Signora Cabrini was fifty-two when Francesca was born, and the tiny baby seemed so fragile at birth that she was carried to the church for baptism at once. No one would have ventured to predict then that she would not only survive but live out sixty-seven extraordinarily active and productive years. Villagers and members of the family recalled later that just before her birth a flock of white doves circled around high above the house, and one of them dropped down to nestle in the vines that covered the walls.

The father took the bird, showed it to his children, then released it to fly away.

Since the mother had so many cares, the oldest daughter, Rosa, assumed charge of the newest arrival. She made the little Cecchina, for so the family called the baby, her companion, carried her on errands around the village, later taught her to knit and sew, and gave her religious instruction. In preparation for her future career as a teacher, Rosa was inclined to be severe. Her small sister's nature was quite the reverse; Cecchina was gay and smiling and teachable. Agostino was in the habit of reading aloud to his children, all gathered together in the big kitchen. He often read from a book of missionary stories, which fired little Cecchina's imagination. In her play, her dolls became holy nuns. When she went on a visit to her uncle, a priest who lived beside a swift canal, she made little boats of paper, dropped violets in them, called the flowers missionaries, and launched them to sail off to India and China. Once, playing thus, she tumbled into the water, but was quickly rescued and suffered only shock from the accident.

At thirteen Francesca was sent to a private school kept by the Daughters of the Sacred Heart. Here she remained for five years, taking the course that led to a teacher's certificate. Rosa had by this time been teaching for some years. At eighteen Francesca passed her examinations,

Francesca was offered a temporary position as substitute teacher in a village school, a mile or so away. Thankful for this chance to practice her profession, she accepted, learning much from her brief experience. She then again applied for admission to the convent of the Daughters of the Sacred Heart, and might have been accepted, for her health was now much improved. However, the rector of the parish, Father Antonio Serrati, had been observing her ardent spirit of service and was making other plans for her future. He therefore advised the Mother Superior to turn her down once more.

Father Serrati, soon to be Monsignor Serrati, was to remain Francesca's lifelong friend and adviser. From the start he had great confidence in her abilities, and now he gave her a most difficult task. She was to go to a disorganized and badly run orphanage in the nearby town of Cadogno, called the House of Providence. It had been started by two wholly incompetent laywomen, one of whom had given the money for its endowment. Now Francesca was charged "to put things right," a large order in view of her youth-she was but twenty-four-and the complicated human factors in the situation. The next six years were a period of training in tact and diplomacy, as well as in the everyday, practical problems of running such an institution. She worked quietly and effectively, in the face of jealous opposition, devoting herself to the young girls under her supervision and winning their affection and cooperation. Francesca assumed the nun's habit, and in three years took her vows. By this time her ecclesiastical superiors were impressed by her performance and made her Mother Superior of the institution. For three years more she carried on, and then, as the foundress had grown more and more erratic, the House of Providence was dissolved. Francesca had under her at the time seven young nuns whom she had trained. Now they were all homeless.

At this juncture the bishop of Lodi sent for her and offered a suggestion that was to determine the nun's life work. He wished her to found a missionary order of women to serve in his diocese. She accepted the opportunity gratefully and soon discovered a house which she thought suitable, an abandoned Franciscan friary in Cadogno. The building was purchased, the sisters moved in and began to make the place habitable. Almost immediately it became a busy hive of activity. They received orphans and foundlings, opened a day school to help pay expenses, started classes in needlework and sold their fine embroidery to earn a little more money. Meanwhile, in the midst of superintending all these activities, Francesca, now Mother Cabrini, was drawing up a simple rule for the institute. As one patron, she chose St. Francis de Sales, and as another, her own name saint, St. Francis Xavier. The rule was simple, and the habit she devised for the hard-working nuns was correspondingly simple, without the luxury of elaborate linen or starched headdress. They even carried their rosaries in their pockets, to be less encumbered while going about their tasks. The name chosen for the order was the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart.

With the success of the institute and the growing reputation of its young founder, many postulants came asking for admission, more than the limited quarters could accommodate. The nuns' resources were now, as always, at a low level; nevertheless, expansion seemed necessary. Unable to hire labor, they undertook to be their own builders. One nun was the daughter of a bricklayer, and she showed the others how to lay bricks. The new walls were actually going up under her direction, when the local authorities stepped in and insisted that the walls must be buttressed for safety. The nuns obeyed, and with some outside help went on with the job, knowing they were working to meet a real need. The townspeople could not, of course, remain indifferent in the face of such determination. After two years another mission was started by Mother Cabrini, at Cremona, and then a boarding school for girls at the provincial capital of Milan. The latter was the first of many such schools, which in time were to become a source of income and also of novices to carry on the ever-expanding work. Within seven years seven institutions of various kinds, each founded to meet some critical need, were in operation, all staffed by nuns trained under Mother Cabrini.

In September, 1887, came the nun's first trip to Rome, always a momentous event in the life of any religious. In her case it was to mark the opening of a much broader field of activity. Now, in her late thirties, Mother Cabrini was a woman of note in her own locality, and some rumors of her work had undoubtedly been carried to Rome. Accompanied by a sister, Serafina, she left Cadogno with the dual purpose of seeking papal approval for the order, which so far had functioned merely on the diocesan level, and of opening a house in Rome which might serve as headquarters for future enterprises. While she did not go as an absolute stranger, many another has arrived there with more backing and stayed longer with far less to show.

Within two weeks Mother Cabrini had made contacts in high places, and had several interviews with Cardinal Parocchi, who became her loyal supporter, with full confidence in her sincerity and ability. She was encouraged to continue her foundations elsewhere and charged to establish a free school and kindergarten in the environs of Rome. Pope Leo XIII received her and blessed the work. He was then an old man of seventy-eight, who had occupied the papal throne for ten years and done much to enhance the prestige of the office. Known as the "workingman's Pope" because of his sympathy for the poor and his series of famous encyclicals on social justice, he was also a man of scholarly attainments and cultural interests. He saw Mother Cabrini on many future occasions, always spoke of her with admiration and affection, and sent contributions from his own funds to aid her work.

A new and greater challenge awaited the intrepid nun, a chance to fulfill the old dream of being a missionary to a distant land. A burning question of the day in Italy was the plight of Italians in foreign countries. As a result of hard times at home, millions of them had emigrated to the United States and to South America in the hope of bettering themselves. In the New World they were faced with many cruel situations which they were often helpless to meet. Bishop Scalabrini had written a pamphlet describing their misery, and had been instrumental in establishing St. Raphael's Society for their material assistance, and also a mission of the Congregation of St. Charles Borromeo in New York. Talks with Bishop Scalabrini persuaded Mother Cabrini that this cause was henceforth to be hers.

In America the great tide of immigration had not yet reached its peak, but a steady stream of hopeful humanity from southern Europe, lured by promises and pictures, was flowing into our ports, with little or no provision made for the reception or assimilation of the individual components. Instead, the newcomers fell victim at once to the prejudices of both native-born Americans and the earlier immigrants, who had chiefly been of Irish and German stock. They were also exploited unmercifully by their own padroni, or bosses, after being drawn into the roughest and most dangerous jobs, digging and draining, and the almost equally hazardous indoor work in mills and sweatshops. They tended to cluster in the overcrowded, disease-breeding slums of our cities, areas which were becoming known as "Little Italies." They were in America, but not of it. Both church and family life were sacrificed to mere survival and the struggle to save enough money to return to their native land. Cut off from their accustomed ties, some drifted into the criminal underworld. For the most part, however, they lived forgotten, lonely and homesick, trying to cope with new ways of living without proper direction. "Here we live like animals," wrote one immigrant; "one lives and dies without a priest, without teachers, and without doctors." All in all, the problem was so vast and difficult that no one with a soul less dauntless than Mother Cabrini's would have dreamed of tackling it.

After seeing that the new establishments at Rome were running smoothly and visiting the old centers in Lombardy, Mother Cabrini wrote to Archbishop Corrigan in New York that she was coming to aid him. She was given to understand that a convent or hostel would be prepared, to accommodate the few nuns she would bring.

Unfortunately there was a misunderstanding as to the time of her arrival, and when she and the seven nuns landed in New York on March 31, 1889, they learned that there was no convent ready. They felt they could not afford a hotel, and asked to be taken to an inexpensive lodging house. This turned out to be so dismal and dirty that they avoided the beds and spent the night in prayer and quiet thought. But the nuns were young and full of courage; from this bleak beginning they emerged the next morning to attend Mass. Then they called on the apologetic archbishop and outlined a plan of action. They wished to begin work without delay. A wealthy Italian woman contributed money for the purchase of their first house, and before long an orphanage had opened its doors there. So quickly did they gather a house full of orphans that their funds ran low; to feed the ever-growing brood they must go out to beg. The nuns became familiar figures down on Mulberry Street, in the heart of the city's Little Italy. They trudged from door to door, from shop to shop, asking for anything that could be spared—food, clothing, or money.

With the scene surveyed and the work well begun, Mother Cabrini returned to Italy in July of the same year. She again visited the foundations, stirred up the ardor of the nuns, and had another audience with the Pope, to whom she gave a report of the situation in New York with respect to the Italian colony. Also, while in Rome, she made plans for opening a dormitory for normal-school students, securing the aid of several rich women for this enterprise. The following spring she sailed again for New York, with a fresh group of nuns chosen from the order. Soon after her arrival she concluded arrangements for the purchase from the Jesuits of a house and land, now known as West Park, on the west bank of the Hudson. This rural retreat was to become a veritable paradise for children from the city's slums. Then, with several nuns who had been trained as teachers, she embarked for Nicaragua, where she had been asked to open a school for girls of well-to-do families in the city of Granada. This was accomplished with the approbation of the Nicaraguan government, and Mother Cabrini, accompanied by one nun, started back north overland, curious to see more of the people of Central America. They traveled by rough and primitive means, but the journey was safely achieved. They stopped off for a time in New Orleans and did preparatory work looking to the establishment of a mission. The plight of Italian immigrants in Louisiana was almost as serious as in New York. On reaching New York she chose a little band of courageous nuns to begin work in the southern city. They literally begged their way to New Orleans, for there was no money for train fare. As soon as they had made a very small beginning, Mother Cabrini joined them. With the aid of contributions, they bought a tenement which became known as a place where any Italian in trouble or need could go for help and counsel. A school was established which rapidly became a center for the city's Italian population. The nuns made a practice too of visiting the outlying rural sections where Italians were employed on the great plantations.